RepowerEU plan is short of what is required

RepowerEU is a historical opportunity to combine energy security of supply with energy and climate transition. It requires bolder steps.

The European Commission has just proposed a new RepowerEU plan on the basis of its existing RepowerEU communication in response to the European Council’s call to propose a plan

It was discussed at the European Council yesterday in the context of difficult talks to impose a new round of energy sanctions. The plan is a potentially critical contribution to Europe’s future energy policy but also more broadly to its economic and political integration but it is falling short of expectations and short of what it should really aim to achieve.

Ideally, the EU has to achieve the following objectives:

1. Ensure the sufficient security of supply to all Member States and deal with the implications of the Russian aggression. This may require building emergency responses, coordinating scarce supplies and resources, organising rationing measures and critical infrastructure in record time.

2. Improve the medium-term functioning of the European energy market, which requires building infrastructure and market mechanism to ensure the cleanest and cheapest energy across the EU over the long term.

3. Augment the green transition by accelerating the shift away from fossil fuels across the EU and establish the necessary investments and solidarity mechanisms to achieve our fit for 55 targets ahead of time.

These requires accelerating and overhauling existing European plans and legislations and creating new instruments and decision making bodies and potentially gradually transferring some energy competences to the EU level. The real danger is that European Member States respond to the energy crisis and emergency in an uncoordinated way potentially canibalizing each other’s efforts, increasing the overall costs, weakening the security of supply and the long term vulnerability of the EU’s energy system and strategic infrastructures.

The need for cooperation and centralisation is potentially as acute as it was during the COVID-19 crisis, but the needs are long-lasting and require not only emergency measures. So far the plan is missing both the executive authority to deliver and the financial resources.

I. governance

a. A new role for the commission

DG ENER is playing a more critical role now both for the EU’s critical energy independence and coordinating of energy related policies and infrastructure. In particular, its role is expanding de facto to areas that require greater planning and executive powers:

· to support coordination of demand and flows, possibly through centralised order of energy commodities as the Commission did for the negotiation, contracting and distribution of COVID-19 vaccines. The power granted to the Commission during COVID crisis should be granted again for managing the energy crisis.

· to provide technical support for projects on the implementation phase to ensure the best interoperability of energy investments and standards across the EU

· to consolidate external negotiations, partnerships and contracting with energy suppliers to avoid anti-cooperative behaviour between Member States and to maximise the negotiation power.

· To organise crisis management and coordination of actions in the event of rationing to ensure comparable treatment across the EU and preserve the level playing field in the single market.

· To coordinate and adapt competition rules for energy policy at times of great investment needs and national government support measures and mandates.

b. A crisis management role for the Council of Energy Ministers

· The need for Member State coordination on energy issues has increased substantially and must organised accordingly. This requires Energy Ministers in the EU to be able to act rapidly and take coordinated decision.

· The council of Energy Minister could therefore be upgraded and enjoy a dedicated secretariat to prepare its meetings its decisions along the format of the Eurogroup. The Eurogroup Working Group Secretariat is organised by the European Commission and so should the Energy Minister Council.

· Given potentially drastic decisions to come in form of energy rationing, these decisions cannot be left entirely to individual Member states and need to be coordinated if not directed at the European level.

II. legislation / Initiatives / instruments

There are a number of legislative processes and European strategies that should come together to upgrade considerably the EU’s energy approach. This would also require revisions in approaches that have so far been undertaken by individual Member States (Hydrogen for example).

There are important identification of critical energy infrastructure in the Commission’s communication in particular electric and hydrogen infrastructure. This work has be to developed further (it will be for Hydrogen by the spring of 2023) but it also probably requires financing to bypass national resistance to these infrastructures.

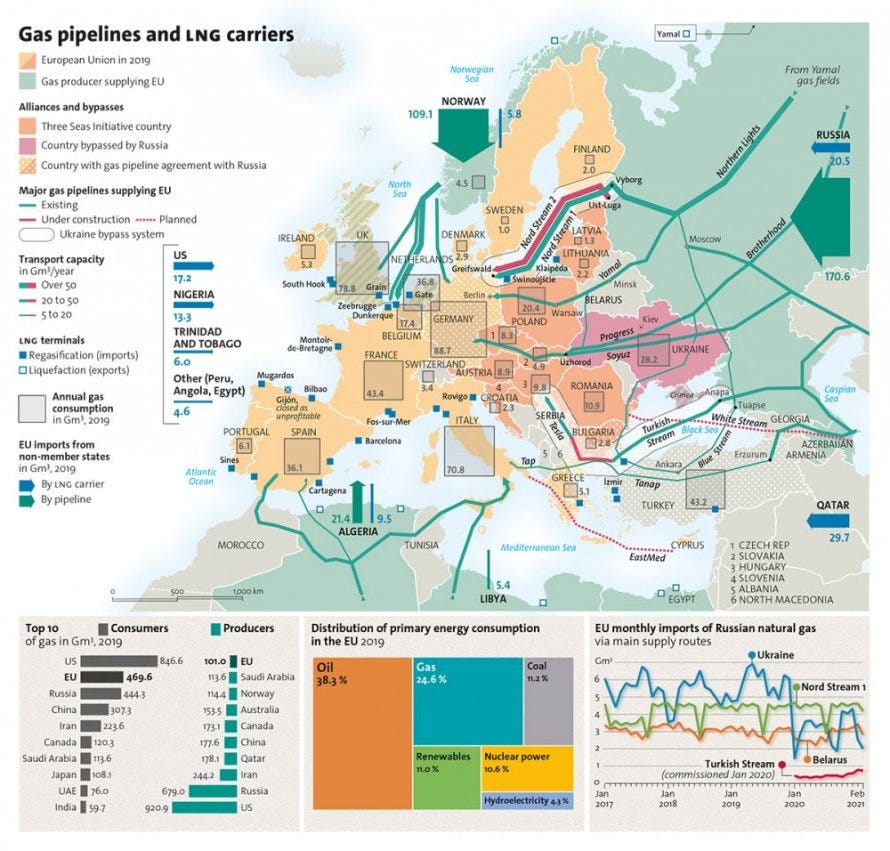

At the moment, energy infrastructures, for example on LNG terminals and interconnectors are essentially at the national level.

b. Trans-European networks for energy

c. LNG strategy

d. Hydrogen strategy

e. Projects of common interests

III. Financing

The Commission has calculated that is plan would require some EUR 210bn of additional investments and these are probably underestimated given that they are not working on the basis of an effective oil and gas embargo that would certainly increase the overall cost substantially.

a. National room for manoeuvre and the SGP

· The current energy transition and security of supplies needs require massive short term investments. The protection of consumers and businesses to the rise in energy prices requires immediate and coordinated policies. At the moment the Commission is forecasting that current measures amount to some 0.7% of GDP in 2022 and rising.

· The EU has announced that fiscal rules would be suspended by another year until. But there is no progress in sight towards a consensus towards deeper reforms.

· It should also set out guidelines and list of policies and investments that would be discounted from measures of fiscal sustainability in the Commission’s surveillance.

· This would ensure an adequate fiscal response to the current crisis but also create some level-playing field by formalizing policies that are encouraged thereby limiting risks of beggar they neighbour policies or frictions in the single market.

b. European Investment bank financing

· The European Investment has made the bold plan to invest a trillion euro in transition related investments between 2019 and 2030 as part of its Climate Bank Roadmap. This amount could augmented and frontloaded given the emergency.

· In particular, the EIB’s risk tolerance has remained fairly conservative and could be relaxed to increase the maturity and propose more concessional financing to energy savings and security of supplies related invesments.

c. EU budget and instruments

· There are potentially several pockets of EU budget resources that could be mobilised. Projects of Common Interest are eligible for funding from the Connecting Europe Facility (CEF), the EU fund for boosting energy, transport, and digital infrastructure. The new CEF programme for 2021-2027 allocates a total budget of €5.8 billion to the energy sector. In addition to projects of common interest (PCI), it includes a new section to support cross-border projects for renewable energy.

· The Green deal has also proposed to dedicated some financing via its Hydrogen and LNG strategy, which probably warrants more resources.

d. Just transition fund

· Given the scale and speed of the redesign of energy supply chains, it is undoubtable that the current framework of the Just Transition Fund needs to be redesigned. This implies larger and deeper distributional efforts across EU member states but these cannot be accepted without serious and common revision of energy policies.

· The debates that are current taking place to ensure that Hungary would participate in an oil embargo highlights the need for additional resources to ensure rapid energy security in Europe.

e. New common borrowing facility

· Given the size of the investment and distribution needs, it is most probably that the EU will have to embark on financial commitments that go beyond what is achievable with the current MFF. I disagree here with my friend Andre Sapir who suggests that no new financing would be required.

· This will require thinking of common borrowing instruments to undertake this new climate and energy policy and could be based on the legal basis and technology used for the COVID-19 RRF.

· However, the question of own resources of the EU remains outstanding and has not been addressed and it appears unavoidable to set out a new common borrowing plan. The Commission has talked about effectively issuing new ETS quotas, which would provide more revenues but would also weaken the emissions reductions of the EU.

IV. Conclusion

· All in all, the EU is still shy of putting together a plan that is bold and radical enough to meet the current challenges. In the absence of better planning, it is unconceivable that the EU can escalate sanctions on oil and natural gas in the coming months.

· But more worryingly, it also means that the EU is not ready for the possibility of supply interruptions from Russia over the winter. This lack of preparation and willingness to entertain bolder steps stands in stark contrast with the centralisation that took place during COVID-19.